June was a busy month, with many friends in town for Scintillation, the small convention in Montreal for which I do programme. It was great to see people again after having to cancel for the last two years! We discussed many great books, including John M. Ford’s Aspects (2022) which is out now, so wonderful to be able to recommend it at last. And I read fifteen books, and I have quite a lot to say about them.

Rosemary Kirstein The Steerswoman (1989)

Re-read for a Scintillation panel. The book remains a delight, as always, the panel was also a delight, with some people who had read the book long ago and others who had read it this year for the first time but were no less enthusiastic for that. The panel was on all four books in the series, and Rosemary sat in the audience occasionally making a note. These are such amazingly good books, such a rich world, such excellent characters. And it’s a good candidate for a series that gets better as it goes along and more is revealed about what’s really going on—some books have questions that are more interesting than the eventual answers, this is not at all the case here. I find new depth every time I re-read.

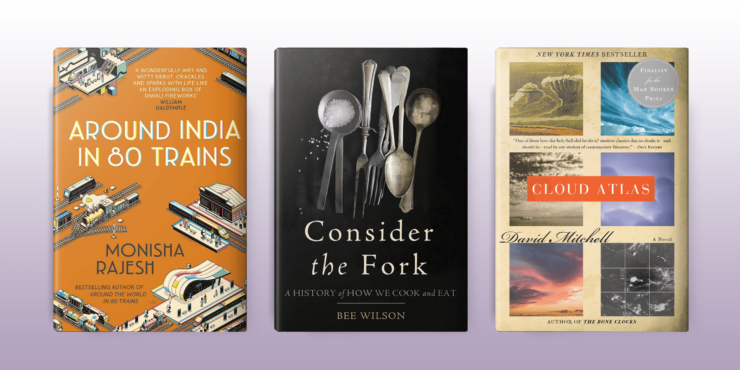

David Mitchell Cloud Atlas (2004)

I am not at all sure what I think of this book, or whether it is successful in what it is doing. Had anyone told me it had xperimental spelng I’m not sure I’d have read it, or at least not yet, but nobody did. The conceit of the book is that it consists of a series of split novellas, moving forward in time, so the book begins and ends with two halves of a novella from the eighteenth century, then there are two from 1919, the 1960s, the 1990s, the near future, and the middle future—this is the only one that is intact. Each new portion has a character read or encounter the material from the previous portion. But I don’t understand what’s supposed to be going on, or whether there is actually any thematic unity. And it’s very difficult to talk about, because the level of writing and engagement in all of it is incredible, but nevertheless the science fiction portions are pretty cliched imaginations of futures, and kind of embarrassing. Even apart from the misguided spelling issue, they are far and away the weakest parts of the book. There is nothing innovative or even particularly interesting about them as science fiction. Nor do they connect to what I have seen of his wider universe, at least not in any visible way—I’d decided it must be in a different universe until I encountered Luisa Rey again in the stunningly brilliant Utopia Avenue, for which see my forthcoming July post. The other parts of Cloud Atlas were great, but it didn’t necessarily feel thematically like a mosaic novel, or like a novel at all, just a set of nested stories. It was certainly a bold thing to do, and his characters in most of the sections were great, if always just slightly verging on satire, but on the whole I… don’t get it. I loved some parts of it, but other parts I slogged through to see get to where I could see what he was doing, which in the end I never figured out. I am very very glad I had read other Mitchell before reading this, because nothing would have persuaded me to read his other (excellent) books if I’d read this first. My advice would be not to start here, and maybe not to go here at all. But probably it’s me not it, and I’m just not old enough for it and I’ll get it on a future read.

Vikram Seth (trans) Three Chinese Poets (1992)

This was an absolute delight, Seth translated three classical Chinese poets, Wang Wei, Du Fu and Li Bai into beautiful English poetry that I loved. I actually read this twice through —it’s short—because I wanted to spend more time with it. All the individual poems are short, and the quality of both thought and translation is really high. I recommend this translation to anyone who likes poetry.

Jules Wake Escape to the Riviera (2016)

This is the second romance novel I’ve read about a woman seeking out her ex so they can get a divorce from the marriage that was never properly ended only to find… well, just what you’d expect, really, that they love each other after all. Excellent France, excellent teenage niece, excellent disabled sister, and Wake is very good at making even a very very implausible romance work. Almost as good as if it was set in Italy.

Claire Tomalin The Young H.G. Wells: Changing the World (2021)

A biography of H.G. Wells that stops before WWI, and looks in detail at his early life and how he made himself who he was. I had no idea he came from such a background of poverty—his mother was a servant—or how entirely self-educated he was. The details of how he came to claw an education out of a situation that would have given him nothing are fascinating, and highlight the “Eloi” and “Morlock” division in a different way. Tomalin is one of the best biographers writing, and in this book she is at the top of her powers. Read this if you’re interested in Wells, or in social conditions in late Victorian England, or in socialism, or in how people change the world.

Monisha Rajesh Around India in 80 Trains (2011)

Fascinating travel book about an English woman whose family originate in Chennai taking eighty trains around India. A travel book is always as good as the narrator, and Rajesh is honest and fun and has a very interesting angle on the country her parents left, but which is still full of her relatives. Lots of interesting India, lots of trains, lots of conversations with strangers and the real feel of a long trip.

Marge Piercy He, She, and It (1991); UK title Body of Glass

Re-read for a Scintillation panel. Neither title is very good for this book, which is science fiction set in a cyberpunk near future that feels very solid in some ways and very wobbly in others. But it has a robot and stories about the golem of Prague. The actual cyber uses the nonsensical “brain goes into computer, user can be killed in system” thing that Gibson came up with and is just as annoying to me now as it always was. The world ruined by climate change was more unusual when I first read it than it is now. The good thing about this book is the thoughtfulness about family and the great characters.

Jane Beaton Welcome to the School by the Sea (2008)

A school story for adults? With an introduction about how we used to have all these school stories and now we don’t have any except magic schools, and surely she’s not the only person who wants them? I’m so there—except sadly this was disappointing. You hear people use the term “headhopping” very loosely, and often when they just mean omni, but this book really had it, starting the paragraph in one character’s POV and ending in another leaving you unsure whose head you were in for the middle part. I read all of it anyway, because I really am a sucker for school stories.

Suzanne Marrs What There Is To Say We Have Said: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and William Maxwell (2011)

Maxwell was an editor at the New Yorker, and I loved his correspondence with Sylvia Townsend Warner, and I quite enjoyed Welty’s correspondence with Ross MacDonald, but this book fizzled a little for me, I’m not sure why. Maybe because they weren’t really discussing writing at the level she did with MacDonald and he did with Warner? There’s a friendship here, but it’s surprisingly mundane. But did you know that he would sometimes send her a stamped addressed postcard with a question and YES/NO and she could just cross it off and drop it in the post? More writers and editors could do with excellent lines of communication like that!

Lindsey Kelk On a Night Like This (2021)

Chicklit, not really set in Italy but it was so good I didn’t mind much. This was delightful, it was genuinely funny and impressively original, while actually being Cinderella all the time. I kept smiling when I was reading this because it was so delightful, and the characters were so good. Doesn’t waste a lot of time on the romance, which is a plus.

Bee Wilson Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat (2012)

This was great, a history of kitchens, cooking, and kitchen implements, written by a British cook and food writer, but with a world-wide focus. There was a lot here I didn’t know and had never considered. Full of facts you’ll want to read aloud to your long suffering family. Really great read.

Dorothy Canfield Fisher Raw Material (1923)

Well, when she says it’s raw material for stories she’s not kidding. This is a series of vignettes and descriptions of people, few of them resolving into actual stories, and most of them unsatisfying in one way or another, but with enough of Canfield’s typical brilliant flashes to keep me reading. Don’t read this, read Hillsboro People if you want short stories, and read her novels. But it’s good to see more of her work becoming available.

Samuel R. Delany Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand (1984)

Re-read. I was having a conversation about how interesting use of pronouns didn’t start with Leckie, and found myself mentioning this book. Then I was talking to someone else about re-reading, and found myself quoting a passage from near the beginning of it. Then someone was asking for worlds without nuclear families, and I explained about how that works in this, and then when I went to bed I felt as if I was already reading it and opened it up. It is full of pyrotechnics. One does not always want to read Delany, any more than one wants cheesecake for every meal, but my goodness he’s good and sometimes just what you were longing for. 1984. Fresh as ever.

Harry Kemelman Sunday the Rabbi Stayed Home (1969)

Another enjoyable mystery where the community is more interesting than the mystery itself. Fun, fast paced, interesting, I continue to go through these quickly and enjoy the experience.

Georgette Heyer The Unknown Ajax (1959)

Re-read, bath book. Regency romance with smugglers, families, mistaken assumptions, a very plausible (for Heyer) romance but somehow I didn’t enjoy this as much at bath-reading speed of a chapter or so a day as I have on previous faster readings. Some of the minor characters are really unpleasant and unkind, and I really noticed that when given time to think. I’m downgrading this one.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

I have much much respect for your opinion on all things literary – but we shall have to agree to disagree about Cloud Atlas… :)

Agreed on Cloud Atlas. So I need to try something else of his.

Also love the Steerswoman books. Do you – or anyone else – have any information on progress of new releases? Several recent belated arrivals (Attolia, the end of Marks’ Elemental Logic quartet) have seeded hope…

I saw Rosemary at Scintillation, and she said she’s writing as fast as she can, but had no actual news. When the next book comes out you will see it here the instant it is available, I will drop everything to read it.

As always, some intriguing books to look into, thank you. I’ve been sitting on a copy of Consider the Fork for a few years now and should really get to it. I’m also prone to badgering family with interesting tidbits from books like this. Have been sitting on a copy of Cloud Atlas for a while, too, but hmm. I did like Slade House, but obviously they’re quite different. (Also, I did recently read Or What You Will and very much enjoyed it :))

Read The Bones Clocks first, really liked it. Then realized, oh this is The Cloud Atlas gut, must read that next. Only I couldn’t get in to it. Glad it isn’t just me. I used to read voraciously but it gets harder and harder. Aging, stress, a degenerative visual disability and the damn intrawebs = the incredible shrinking attention span.

Stars in my pocket like grains of sand was supposed to be the first part of a duology, I thought. What a pity that the sci-fi market didn’t offer enough for Delany to write the sequel. Or, perhaps he lost interest. At any rate, it is a favorite of mine.

I’d have to re-read Cloud Atlas to see if I agree with you, but that’s not likely anytime soon. My memory of it better than your experience. But then, as I said in a past comment, I read the stories in chronological order, not in halves, ending with the future Hawaii episode. Reincarnation and the comet birthmark are part of the key.

One thing that gives me pause… “the stunningly brilliant Utopia Avenue…” I didn’t finish that one. Maybe the shine is coming off Mitchell for me, but I thought it was self-indulgent and fannish. Hope he returns to form.

Nancy P: The reason Delany didn’t write The Splendor and Misery of Bodies, of Cities the sequel to Stars In My Pocket is the AIDS epidemic destroying so much of the gay culture of New York and killing so many of his friends in the late eighties, so that the source material for the world he had built, with its runs and so on, had been lost so painfully that he didn’t feel able to keep writing about it. The SF market would have loved to publish it and still would, had he been able to write it.

Ok fine, you’ve convinced me – time to obtain some copies of Kirstein’s books! Some ten years ago, I did read both Steerswoman and Outskirter’s Secret(I believe on your recommendation on this site!) and while enjoyed, for some reason never got the succeeding books? I need to remedy that now. As well as find new copies of the first two, as they seem to not have survived my transatlantic move.

Have you read Black Swan Green by David Mitchell. That’s one of my favorites. Again, it’s something like a series of linked short stories, but they all have the same protagonist, and they’re much more cohesive than Cloud Atlas.

Jo – I was wondering whether this month you were going to dip your toes into Book 2 of the Aaronovitch Rivers of London series. I read the first one based on your recommendation last month and I really enjoyed it. Very much enjoying the next ….six or so, so far. They definitely have some violence and a high body count that that seems suited to the particular challenges faced by Peter and his boss in magically influenced London and environs.

Peter: I loved Black Swan Green. I read it a few months ago, and wrote about it here at the time. Wonderful book.

Sunspear: I don’t know whether you read Cloud Atlas at all, at least, you certainly read all the words, but you definitely didn’t have the reading experience the author wanted you to have. I see no point in reading it out of order, as it had value it had value in how it connected, or didn’t connect, and in the order Mitchell arranged it in. I don’t know if it worked or not, as it was written, but reading it out of order would be a pale shadow of the intention. I did remember you saying this as I was reading, and asked myself why anyone would deliberately ruin their reading experience that way!

Cloud Atlas was the first David Mitchell I read, and unlike Jo, I felt like I “got it” at the time – I appreciated the stories, and their deft jumps between different genres and story-telling styles, as well as the formalism of the odd structure. I do feel there was a complex message to the whole thing that I wasn’t quite getting – something about both the persistence of systems of human cruelty and of individual resistance and rebellion against them – but perhaps I’d get that a little more clearly on a reread.

It does have ties with his other books – the ingenue daughter shows up as an older woman in his apparently realist novel Black Swan Green, with a belated appreciation for her music teacher’s talent – and I’m probably missing others. The Bone Clocks was the book of his that I really had trouble getting into for the longest time, picking it up and restarting it and dropping it; finally, I suddenly clicked with it at a certain stage in the book – or perhaps because I’d been pushing at it long enough – and swiftly plowed through the rest and enjoyed it.

You’re right that The Unknown Ajax has some nasty people in it. But the last 100 pages or so are a spectacular piece of sustained comedy spiced with drama unequalled in Heyer’s other work. My favorite part is that the two characters with the lowest status among the family and upper servants – Claud and Polyphant – save everybody else’s bacon, and that everyone has to acknowledge it, which unseats both the old and young tyrants in the family. And Aunt Aurelia sweeping in to save the day is the cherry on the cake.

Interesting family dynamic, that the denouement destroys Lord Darracott’s chief claim to dominance – more power and sharper wits than anyone else – and, no sooner is he humbled than Hugo et al. start planning how to set him atop the heap again, even though the myth is now hollow.

As a school stories fan I get what you are saying.

One grown-up “School Story” I liked was the book Educating Alice by the late Alice Steinbach. It’s non-fiction, but awesome as she travels around the world attending different educational things like an Oxford Summer School or a French Cooking School.

Oh, and there was an Ellis Peter’s book set in a folk music summer school. That was pretty cool.

@13. bluejo: I don’t think it ruined my experience at all. It made sense as I was reading it and I wasn’t at a loss when it was over. I simply chose to ignore the author’s gimmick. Perhaps Mitchel overstretched his themes and symbols with the split narrative structure if he left some readers without a sense of closure or satisfaction.

Perhaps reading Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch had an influence on me. Here’s the reading instructions for that book:

“I am very very glad I had read other Mitchell before reading this, because nothing would have persuaded me to read his other (excellent) books if I’d read this first. My advice would be not to start here, and maybe not to go here at all.”

Cloud Atlas is the only Mitchell I’ve read, and had a very similar experience with it. The only positive memory I have of it is laughing darkly at one of the future sections calling all movies “disneys.” I’m relieved you said this, because at least twice I’ve gotten really interested in books you talked about in past columns, only to reject them sadly when I realized they were his. I feel inspired to try one after all!

I loved Cloud Atlas, even though I’d agree the more SFnal parts were the weakest. That said, I think his best book is — I know I’ve said this here before — The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet.

‘I haven’t yet read Utopia Avenue. I have a sort of allergy to Rock and Roll books, but I will get to it eventually.

I loved Cloud Atlas. It made me read almost all of David Mitchell’s books. (Two still two to go.) And I have appreciated them in varying degrees but they were all worth the read. The Steerswoman books are fantastic. Haven’t read them since they came out. Not sure if I’ve read the 4th one. So, I should get back and re-read. And you talked about one of my top five SF books – Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. He did publish a novella size amount of the second novel written before AIDS dropped it’s pall over all of us. Except for your feelings about cyberpunk – you have terrific taste. (Meaning of course you and I often agree!)

As it happens I’m just reading the volume devoted to Marge Piercy in PM Press’s Outspoken Authors series, which I find very valuable in general. I’ve been reading a bunch of those; they introduced me to a number of authors I didn’t know (I missed a lot along the way). There’s an essay on abortion by Marge Piercy that is probably harder-hitting now than it was when written.

Hoping to read Tomalin quite soon – even more so now, in view of your comments – but I’m mainly finishing up some Hugo-related reading first. Things are getting a little out of hand at the moment. Somehow my family sees books lying about and feels like this means they need to buy me more. I can’t explain it. (If I were a cat, maybe. [I’m not.])

I enjoyed the pretty fancy Cloud Atlas, and much other Mitchell. I think I started with that one. But I don’t recall experimental spelling. Been a while I guess. (I also like Oulipo, and puzzles.)

I just finished reading all 4 of the books in The Steerswoman series and really enjoyed them. The Harry Kemelman books are in my to-be-read queue. Maybe I’ll start that series this weekend after I finish the final book in Ellis Peter’s The Chronicles of Brother Cadfael series, which I have really enjoyed. The descriptions of life in 12th century England are as interesting as the mysteries.

I’m finishing up Brother Cadfael’s Penance and then I’ll try the Steerswoman series, which is in my electronic TBR pile on my Kindle. Re-reading the Cadfael Books has me itching to re-watch the series, which I recall had quite good production values.

Cloud Atlas was so bad that it makes me not interested in his other books. It failed in so many ways.

I like complicated structures, but the pyramid just didn’t do anything. There were some weak connections between the layers that were tricky to figure out, then weren’t useful or satisfying. Coming back down the pyramid, the second halves didn’t seem to rely on the upper layers at all. I bet if you read each story straight through as a staircase, it wouldn’t be much different. Compare that to Cosmonaut Keep (Ken MacLeod), where alternating chapters go forward and backward in time, then resolve.

The SF parts were really weak. It read like he didn’t think SF was hard, that you could just make stuff up. Merging chaebol and Juche? That is nonsense. I need sold on how and why that works. It was insulting to the reader.

Finally, the “top” story may be the most nihilistic thing I’ve ever read. Due to random bad luck, civilization is destroyed. The whole book has been building up story, passing it on into the future, and in the end all story is lost. Then after knowing that all of the stories are futile in the end, we are expected to read the second half of the book? Samuel Beckett is more hopeful than this.

I’m not going to spend any more time on David Mitchell’s books. He’s wasted his allotment of my attention.

Wunder — I’m sure I’d feel the same if this were the only thing of his I had read. I’m so glad I didn’t start here.